Ecocriticism can generate a joy that is otherwise hard-fought or missing from the serious facts of our warming climate, said LMC Associate Professor Kristi McKim.

Ecocriticism is an interdisciplinary field that explores the relationship between humans and the environment through literature, culture, and the arts. It questions how media represents nature and how those representations influence our perceptions and actions toward the natural world.

"Ecocriticism counteracts centuries of anthropocentrism," said Kristi McKim, an associate professor and ecocritical film scholar at Georgia Tech's School of Literature, Media, and Communication (LMC). "When we screen or read something in an ecocritical way, we regard the plants, animals, and atmosphere with the same attention we habitually give to human characters."

The art of ecocriticism is growing in response to our changing world. Hotter summers, stronger storms, and melting glaciers can spark anxiety and shape the way we create and consume media. But talking and thinking about the environment can also inspire change in a joyful way, McKim explained.

"Ecocriticism offers a way to engage with these problems through a lens of appreciation, curiosity, and wonder. Yes, there is a lot to lose. But what a joy and delight that we have it to lose."

How Does Ecocriticism Inspire Change?

Ecocriticism challenges us to see nature not just as a backdrop for human activities but as a character with its own agency. Doing so encourages us to — hopefully! — rethink our interactions with the environment and reflect on our treatment of the natural world.

Picture this: two movies, one a summer fling, the other a Christmas romance. At their core, both narratives are the same — two people falling in love. However, shots of sunny beaches versus snow-covered trees shape two very different stories.

How? And why? Even when it's at our periphery, the natural world powerfully influences the way we feel. So, what could happen if we start to pay attention (and notice the white Christmases from our childhood might not happen again)?

"The first step to making positive change for the environment, whether it be who we vote for or the policies we support, is expanding who we see. In that way, there's a nice affinity between social justice and ecocriticism because at the heart of both projects is care," McKim said.

"However, it's important that the noticing doesn't become an end unto itself, but rather a gateway toward considering who counts in the world and our connection to all life forms. It's staggering that we humans should continually act as if we are not in reciprocal relationships with every creature around us. But film cameras and screens can help us cultivate the attention we then exercise beyond the theater.

"There is no action before there is care, and care requires attention. That's where ecocinema can powerfully shape the world."

McKim points to Robin Wall Kimmerer, the author of Braiding Sweetgrass, for an example of moving from media to the real world. In her book, Kimmerer encourages growing a garden as a good first step toward practicing our attention to the slow routines of the natural world.

“Planting a seed and nourishing its growth is future-oriented,” McKim said. "And this growth becomes, for me at least, a small-scale real reminder that the world is still OK and that all isn’t lost. Our air can still harbor growth, and the soil still has the potential to be a home for a seedling. And all of the things that feel hard can change for the better."

Ecocriticism at Georgia Tech

Ecocriticism also has the power to inspire change by fostering conversations that encourage people to see the environment as an integral part of their lives.

"Other than when we smell a flower or notice a branch on the ground, most of us walk past thousands of different plant species every day and don't pay them any attention," said Luke Rodewald, a Marion L. Brittain postdoctoral scholar in LMC.

"But one of the most powerful things you can do as a person is just engage others in conversation. If there's something that you care about, it's easy to find ways to get them to care about it as well."

Rodewald is teaching a writing, rhetoric, and communication course at Georgia Tech that focuses on plants as a common theme. Throughout the semester, students study how writers and creators draw their attention to plants in their work — organisms that are frequently overlooked, Rodewald said.

Then, Rodewald introduces the idea of plant intelligence, a growing field of study in botany and the humanities. He challenges his students to write about and communicate an idea "that may seem wacky to some people, including themselves."

The goal is to learn how to approach such a topic in a way that invites people in rather than making them walk away, a task that requires maintaining an open mind, thinking critically, and, hopefully, learning how to meet people in the middle when it comes to climate and environment conversations they may have in the future.

These skills are important because when people realize how issues impact them personally, they are more likely to act Rodewald said.

For example, he originally comes from a community where climate change is considered as real as "the boogeyman or Santa Claus," but the issues it causes, such as topsoil erosion and drought, are top of mind.

"So, it's about finding those connection points and feeling equipped to engage people in conversation about that middle common ground, where the person doesn't shut down because you've met them at some point that they want to talk about as well," Rodewald said.

Read and Watch

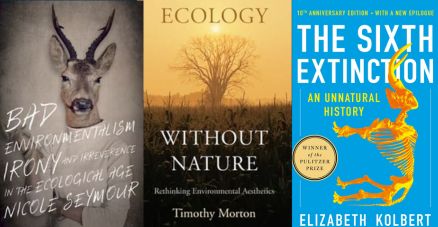

Rodewald recommends these texts as an introduction into environmental literature and ecocriticism theory.

Environmental Literature

The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History by Elizabeth Kolbert

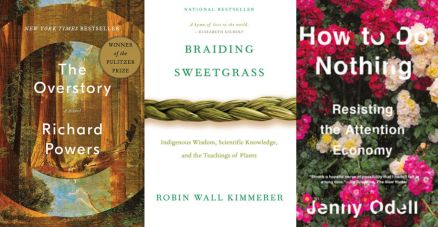

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer

The Overstory by Richard Powers

Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape by Lauret Savoy

Ecocriticism Theory

Bad Environmentalism by Nicole Seymour

Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor by Rob Nixon

Ecology Without Nature by Timothy Morton

The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives by Macarena Gómez-Barris

Along with Braiding Sweetgrass and The Overstory, McKim also recommends reading Jenny Odell's How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy and poetry by the U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón.

Additionally, she suggests watching these films, which are not "rhetorically eco-cinematic, but convey, through fiction, how our human flourishing is inextricable from that of the plants and nonhuman creatures around us."

- Nope (Jordan Peele, 2022)

- Princess Mononoke (Hayao Miyazaki, 1997)

- First Cow (Kelly Reichardt, 2019)

- The Virgin Suicides (Sofia Coppola, 1999) or Marie Antoinette (Coppola, 2006)

- Passing (Rebecca Hall, 2021)

- Petite Maman (Céline Sciamma, 2022)