Can you tell what someone is feeling based on their facial expression?

Proponents of emotion AI — a type of artificial intelligence that analyzes facial expressions, text, voice, and other cues to infer emotions — say it can do just that.

Georgia Tech researcher Noura Howell, who received an NSF CAREER award to study emotion AI in 2024, said the technology has a number of shortfalls that can lead to inaccurate results. Like generative AI, emotion AI is also subject to bias, and its use raises ethical and privacy concerns.

Despite these shortcomings, Howell said emotion AI has quietly shaped decisions in areas like hiring, education, mental health, and public safety in recent years.

Yet most people don’t know it exists.

Howell and Digital Media Ph.D. students Xingyu Li and Alexandra “Allie” Teixeira Riggs in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication are working to change that. They held workshops across Atlanta over the last two months, giving participants a rare opportunity to try emotion AI for themselves — and then share their impressions, ideas, and concerns.

Community Workshops Raise Understanding and Awareness

“People know about web search algorithms, they know about generative AI like ChatGPT, but very few people know about emotion AI,” said Li.

Companies and organizations that use emotion AI aren’t currently required to disclose it. Without that knowledge — or firsthand experience with the technology — Li said it’s very difficult for people to develop informed opinions about the technology’s limitations and ethical implications.

“It’s important that everyone has a say, because this technology affects people’s lives,” Li added.

Li and Riggs said the workshops had two main goals: to increase public awareness and understanding of emotion AI, and to gather feedback from participants based on their direct experience with the technology. This experiential approach, Riggs said, sets their research apart.

“Rather than just critiquing the idea of emotion AI, participants got to try it out and reflect on the experience — on what’s happening with the technology,” said Riggs.

After trying emotion AI, participants answered questions about their experience and used drawing tools or clay to create a design that represents the future of emotion AI as they imagine it.

The researchers believe this kind of rich, creative feedback can help them better understand how diverse groups perceive emotion AI, what concerns they have, and how the technology might be used in ways that are both ethical and beneficial.

Building an Emotion AI

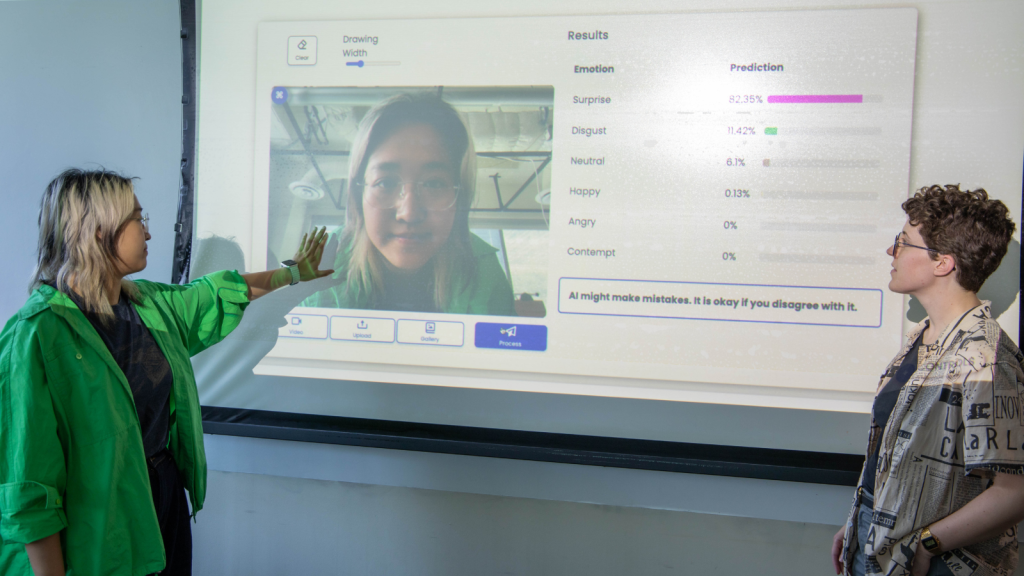

Because most emotion AI systems are proprietary, Li and another Georgia Tech colleague, Zhiming Dai, built their own for workshop participants to explore. They based their system on the most common design, which uses facial recognition — the same technology used to unlock many phones — to analyze facial expressions and infer emotional states.

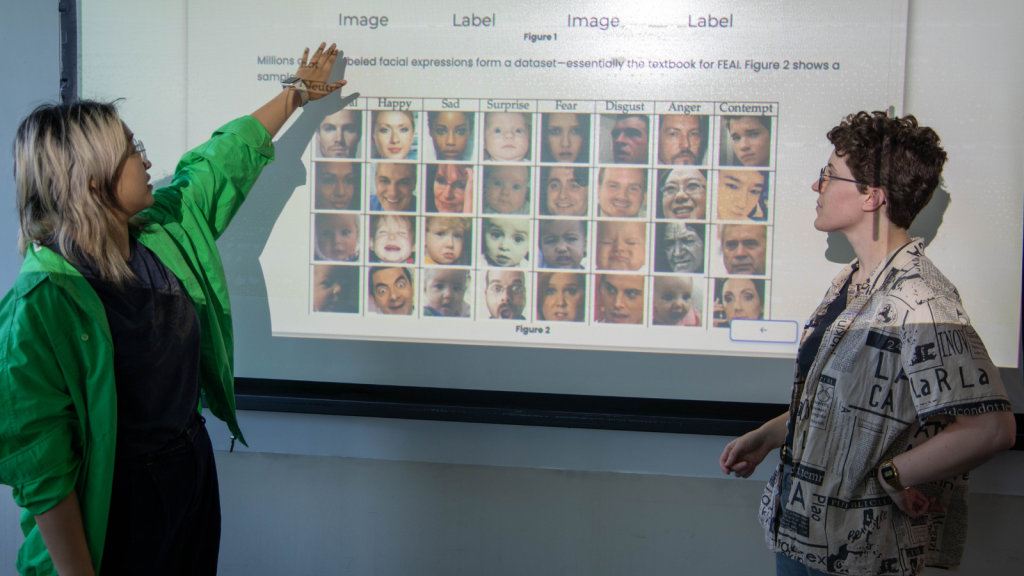

Like most AI, emotion AI must be “trained” using a dataset. Li and Dai used a widely adopted dataset of facial expressions labeled with emotions like “surprised,” “sad,” or “angry.”

“Workshop participants developed their own understanding by using our emotion AI system,” said Li. “We encouraged them to reflect, to share their feelings and concerns."

A Technology ‘Fraught With Ethical Concerns and Challenges’

Although they haven't finished analyzing their data, Li and Riggs say they’re already seeing common themes in participants’ responses.

“Many people challenged the basic idea that you can infer someone’s emotions from their expression alone — and they should,” said Li. “Facial expressions are very important to understanding a person's emotional state, but humans also take into account things like the social and cultural context, the person’s body language, and our knowledge of their habits and personality.”

Participants have also pointed out that what’s considered an “appropriate” emotional expression can vary widely among cultures, age groups, and social settings — nuances that emotion AI often fails to capture.

Emotion is also performative, Riggs noted. In situations like job interviews, people may intentionally display certain emotions while suppressing others. Most emotion AI systems lack the contextual awareness to account for this.

Despite these concerns, Li says investment in the emotion AI market is projected to double in the next few years — from $3.7 billion in 2024 to $7 billion by 2029 — with applications in recruitment, advertising, education, mental health care, and more.

“Emotion AI is fraught with ethical concerns and challenges,” said Li. “And it’s not going away. That’s why this work is so important.”

The School of Literature, Media, and Communication is a unit of the Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts.

Posted July 17, 2025

'No Hard Truths' in Human Emotion

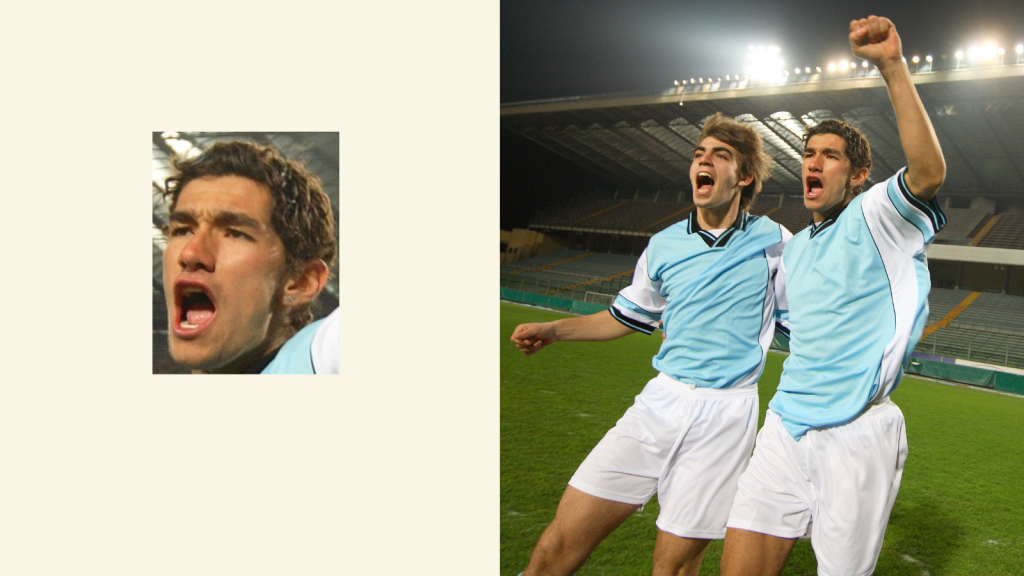

Take a look at the picture below. Can you describe this person’s emotional state?

What if your answer could shape decisions about their job prospects, education, or even public safety? With so much at stake, you might hesitate — and you’d be right to.

“There are no hard truths when it comes to human emotions,” said Li. “When all we have is a snapshot of the face, with no external context, it’s easy to misread.”

For example, in the image above, the snapshot on the left might appear to show anger. But the full context, shown on the right, reveals a different — and more likely — interpretation.