History books are full of the exploits of powerful people. But Christopher Lawton, a lecturer in Georgia Tech’s School of History and Sociology, believes everyone’s story should be told — especially those who had little control over their own while alive.

Lawton is a historian focused on uncovering the names and narratives of enslaved people who lived in Georgia. Often, their first names appear only as data points in court records, listed as the property of the men and women who owned them. Lawton and the students in his Early U.S. History class are working to fix that.

"While their white counterparts were being written about in history books, enslaved people were listed as property without last names, familial relations, or possessions of their own,” says Delainey Foster, a second-year physics student in Lawton’s course. “It challenged my knowledge of U.S. history and questioned how much I actually knew when there was an entire group's perspective missing from our textbooks.”

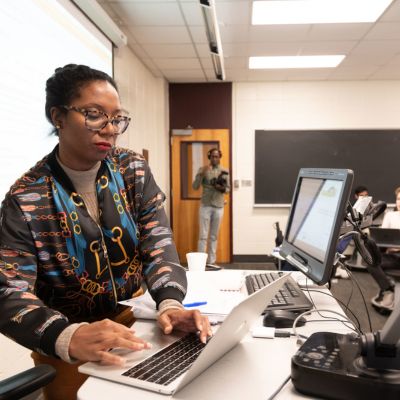

Students in Lawton's Fall 2023 class

Unearthing Identities

Lawton’s students spent the semester combing through digital archives and recording names, ages, locations, and any other information they could glean from the scant reports and cryptic cursive. Then, they translated the data into stories, publishing biographies of the enslaved people on Lawton's website.

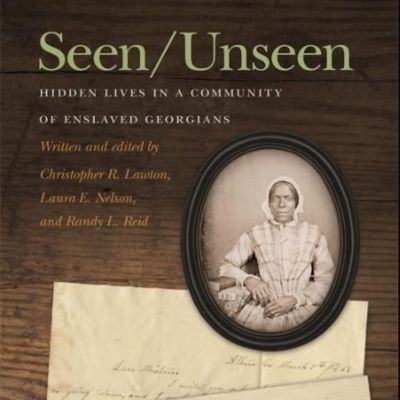

The first entries were from Lawton's book, Seen/Unseen: Hidden Lives in a Community of Enslaved Georgians, co-authored with Laura Nelson at Princeton and Randy Reid at Athens Academy. The snippets share details both mundane and humanizing: Bob Scott worked as a courier, Aggy Carter Mills had more than 200 guests at her wedding.

“Sometimes we can write a full paragraph about the person, and sometimes we can only write one or two sentences,” Lawton says. “But how much we write is in some ways less important than the fact that we write it. Just being able to find and record a name, or a small bit of information, is an invaluable act of reclamation and recognition.”

Lawton previously taught at the University of Georgia, where his students collected data on nearly 10,000 enslaved people in Clarke County. Now, he’s doing the same for Fulton County. While far from all of them will get written biographies, undergraduates in his course have documented the identities of over 700 people who were enslaved in the area this semester alone. They added 11 new biographies to the website in the fall, and Lawton hopes to have 25 to 30 more by the summer.

Christopher Lawton

Increasing Accessibility

Lawton’s work is part of a larger project called Enslaved.org, for which he and his co-authors are partners on a $350,000 National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH) grant awarded this year. Enslaved.org collects and connects projects such as Lawton’s from around the country to create a comprehensive database of information on the U.S. slave trade that individuals and research teams can draw from.

Lawton, Nelson, Reid, and Melanie Pavich, a project partner at Mercer University, will use their portion of the NEH grant to hire Georgia Tech students to clean, organize, and integrate the data they’ve collected into the rest of the Enslaved.org project so others can access and learn from it too.

“Georgia Tech students are uniquely qualified to do this important work,” Lawton says. “Because it's not only about learning to research the past but also intertwining the humanities with technology and place- and project-based learning."

Enhancing History

For example, Dev Patel, a second-year industrial engineering student in Lawton’s course, says he’s interested in exploring the intersection of historical research and artificial intelligence (AI).

“The idea of leveraging AI to identify and document instances of slavery holds much promise for enhancing archival research,” Patel says. “I’m open to staying engaged with the project and discovering new ways technology can aid in unearthing and preserving our past.”

While enslaved people who were alive during emancipation are listed in later census and tax records and can be traced through peoples’ family history, those who lived and died while they were enslaved are not. AI and projects like Lawton’s may someday help expand the record for Georgia.

"We have a responsibility to all past Georgians and a duty to tell their stories carefully and accurately,” Lawton says. “These people were here. They survived, and we have lessons to learn from them.”