Why did Peru’s popular interactive science museum disappear? Alejandra Ruiz León, a Ph.D. candidate in Georgia Tech’s School of History and Sociology, asks this in a new article published in Cultures of Science.

The paper examines the rise and fall of TECNO-ITINTEC, an interactive science museum established in Lima, Peru in 1979 and dismantled in 1993, packed up and stored away in empty cages at the Lima Zoo.

Through years of archival research and more than 50 interviews — including with a Peruvian president who was on the board of the institute that founded the museum — Ruiz León’s dissertation charts the political context of the museum’s creation and closure.

In the article, she argues the museum wasn’t shut down due to random circumstances or changes in demand, but through specific government decisions, which she describes as bureaucratic dismantling, during Alberto Fujimori’s time as president in the early 1990s.

“The Fujimori administration promoted austerity, privatization, and a technocratic model of governance that marginalized public initiatives not deemed economically productive. In this new vision of the state, the museum, and the institute, were not a strategic asset but a dispensable remnant of a previous era,” she writes.

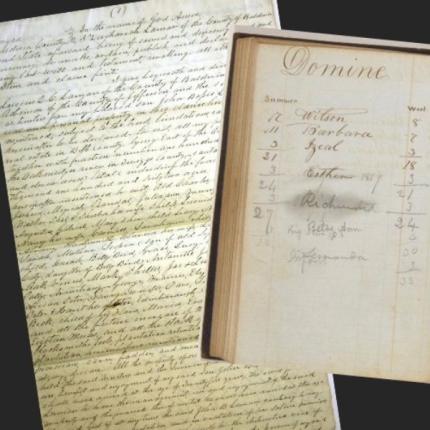

Reporting on the closure of the Institute in Gestión, Newspaper of Economy and Business. The headline in Spanish reads: "The function of the ITINTEC will pass to the Ministry of the Presidency: research tasks and technological development will be transferred to universities and the private sector." Image courtesy of the National Library of Peru.

Why did the museum close?

By the early 1990s, TECNO-ITINTEC had survived Peru’s transition from military dictatorship to democracy and one of the most severe economic crises in Peruvian history. Still, its visitor numbers remained steady, Ruiz León said.

But in April 1992, Fujimori dissolved Congress, moved legislative powers to the executive branch, and announced a state of emergency. The museum’s closing followed soon after, in a “sudden, bureaucratic, and opaque” way, she writes.

“Appeals submitted by former staff and interested institutions were either ignored or indefinitely deferred; instead, decisions were implemented through presidential mandates without further justification or plans.”

The INTEC Board of Directors recorded no meeting minutes in the final year, and the museum was one of many public institutions shuttered during Fujimori’s time in office.

“There was agency in closing the museum — it wasn’t just a mistake,” Ruiz León said.

“Peru was an early adopter in this trend toward interactive science museums, and it vanished for a reason.”

Ruiz León presenting her work at the Peru Conference at Harvard 2025: Tough Conversations for Building Progress.

History of Technology and Science at Georgia Tech

Ruiz León’s article is based on her dissertation, Caged Knowledge, which was written as part of her doctorate in the History and Sociology of Technology and Science. Her research included fellowships at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia and the Deutsches Museum in Munich, Germany.

She said she was drawn to the story because museums are a unique window into how science is practiced outside of typical academic settings.

“It’s like a time capsule for science because you are not only studying scientists but also the audience and what they were learning. Why were they learning it? What experiments were they doing? Why was it important?”

But very little has been written in-depth on the museum or the institute that created it since the 1970s, Ruiz León said. “It’s like everyone forgot about it. But now I’m writing this.”

She hopes the story sparks conversations in Peru and has already shared it at the Peru Conference at Harvard 2025: Tough Conversations for Building Progress.

“In Peru, we tend to be more fatalistic and say things like, ‘Oh, we never have good things.’ But this shows that no, we actually had good things. They just disappear,” Ruiz León said.

“A lot of people may think this is just a Peruvian story. But it reflects many of the trends we see in how museums can be so fragile. Maybe we see them as historical institutions, but they can also quickly disappear.”

“The bureaucratic dismantling of TECNO-ITINTEC (1979–1993): The politics of science popularization and the first interactive science museum in South America” was published in Cultures of Science in November 2025. It is available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/20966083251397564